Overview

Southeast Asia is undergoing a rapid transition from a fragmented voluntary carbon market into a more sophisticated, policy-driven carbon ecosystem. Following several rounds of defining and updating their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), Southeast Asian countries are building stronger policy and institutional environments to mitigate their emissions. These efforts are focused on integrating NDC goals into national and sectoral strategies and creating regulatory frameworks–such as national registries, carbon trading regulations, MRV systems, and emerging ETS structures–that allow project-based mechanisms to thrive.

As these frameworks develop, carbon projects that align with these policies and strategies are better positioned to gain support from their host government. Yet policy recognition increasingly outpaces actual implementation, a notable emerging trend. Many standards are acknowledged in national frameworks, but only a smaller subset has widespread implementation on the ground.

As Southeast Asian carbon markets develop, global businesses and stakeholders are witnessing a shift from pilot-level initiatives toward more scalable, investment-grade opportunities across the entire carbon services value chain. What was once a loose voluntary ecosystem is now being shaped by country-driven regulatory frameworks, especially the introduction of national registries and government-defined rules for how carbon projects must be developed and reported. This shift creates a structured environment, making it essential for businesses to navigate each country’s system with a deliberate and coordinated strategy. In this context, project developers, investors, and technical service providers must tailor their project design, financing structures, certification pathways, and MRV strategies to align with country-specific frameworks, opening significant commercial opportunities for firms that can offer bespoke advisory, legal, and technical services, such as regulatory due diligence, standard selection, carbon accounting, and market-readiness assessments among others. Stakeholders that are able to provide these customized capabilities will be best positioned to guide project proponents through increasingly formalized market requirements to secure high-quality credits.

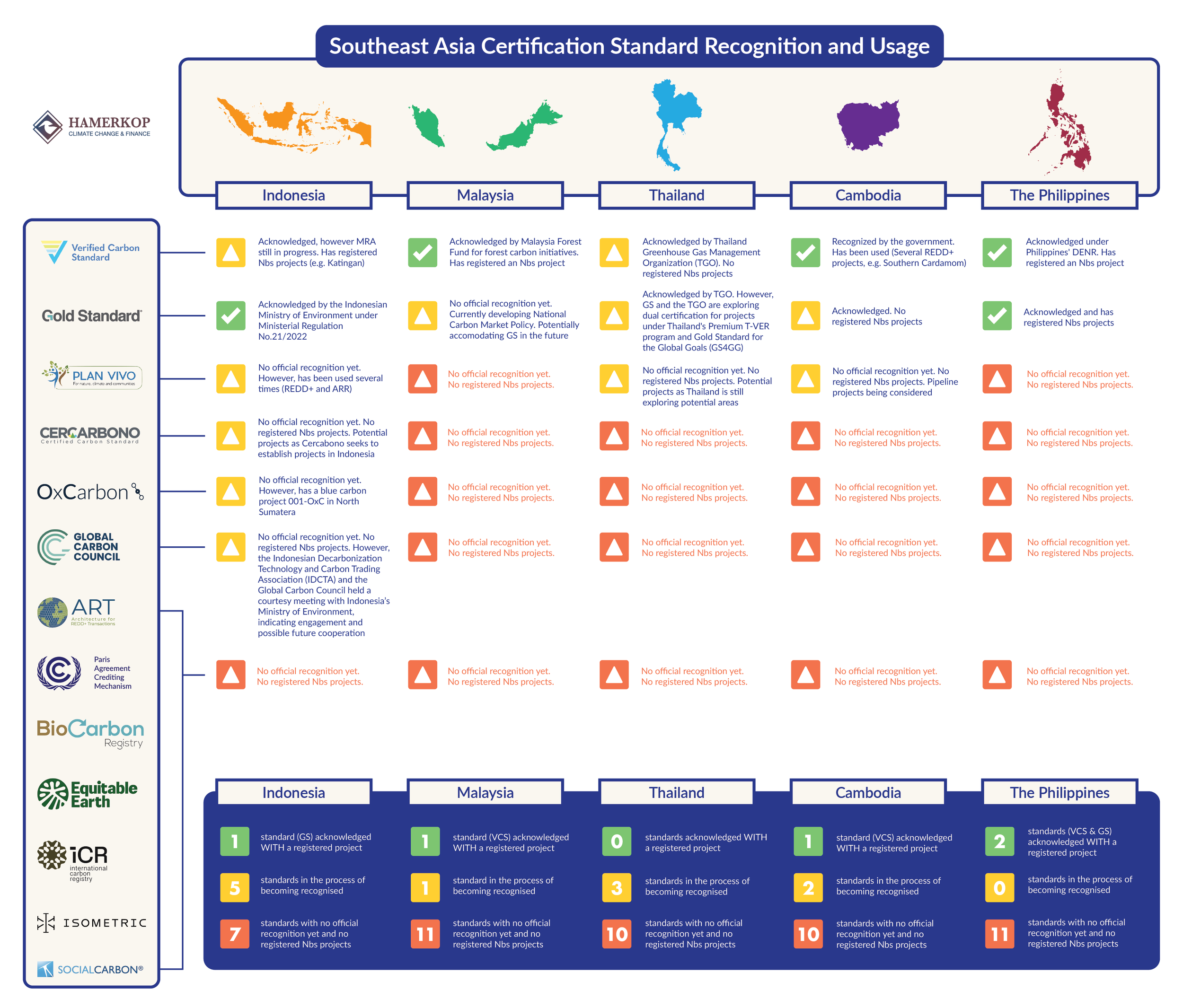

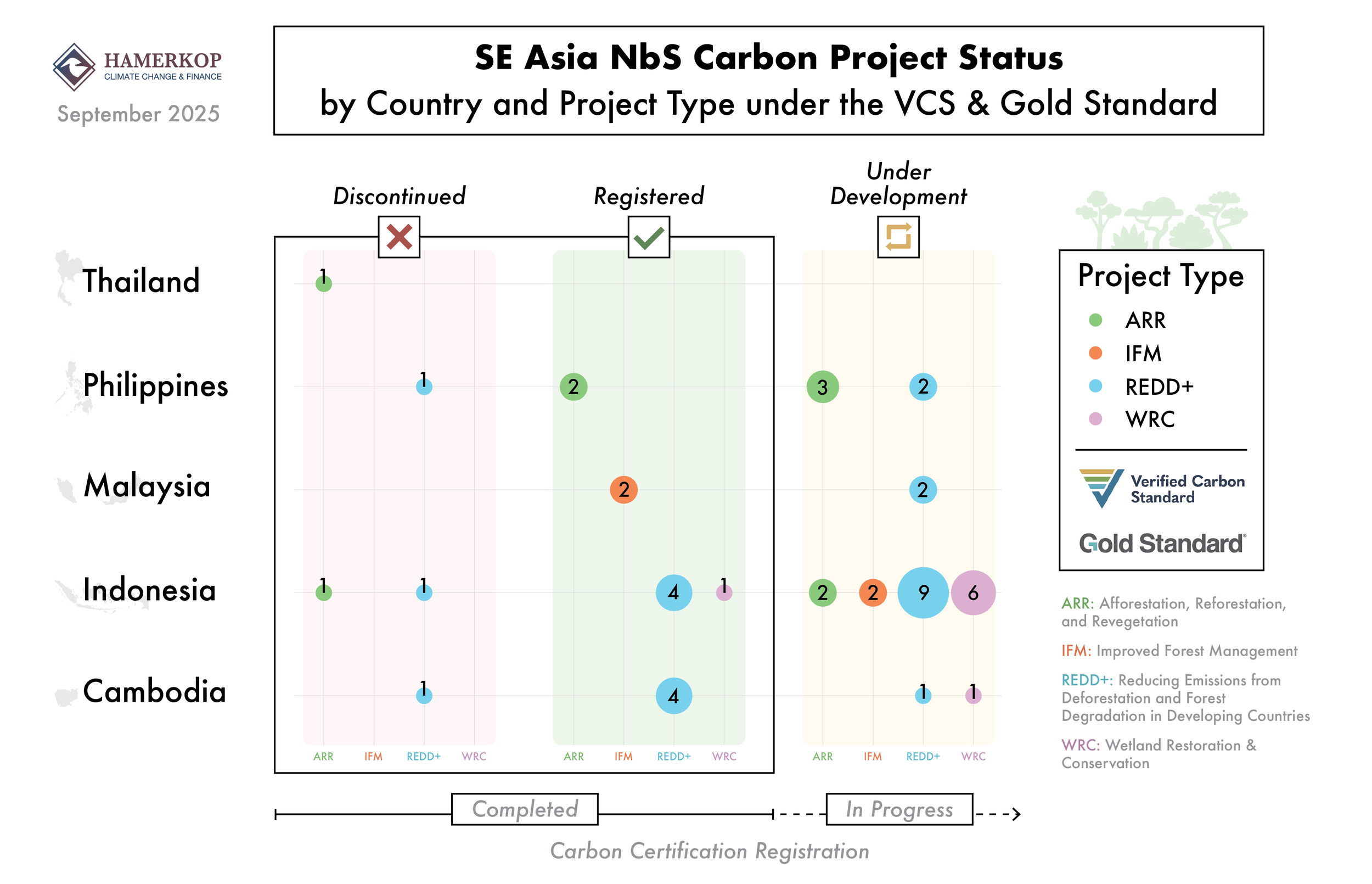

To assist decision-makers in navigating this landscape, we analyzed the usage and recognition of 13 certification standards for nature-based solutions (NbS) across five countries: Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, and The Philippines, based on each one’s policy/strategy and NDC targets. These countries were selected for their demonstrated willingness to tap into the carbon market and their potential to host a diverse range of NbS projects: afforestation, reforestation and revegetation (ARR), Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD+), improved forest management (IFM), and wetland restoration. The following certification standards were selected as the most relevant to NbS and to the region:

Verified Carbon Standard (VCS)

Gold Standard (GS)

Plan Vivo

Equitable Earth

Architecture for REDD+ Transactions - The REDD+ Environmental Excellence Standard (ART-TREES)

Cercarbono

Isometric

Biocarbon Standard

Global Carbon Council (GCC)

International Carbon Registry

OxCarbon

Social Carbon

Article 6.4’s Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism (PACM)

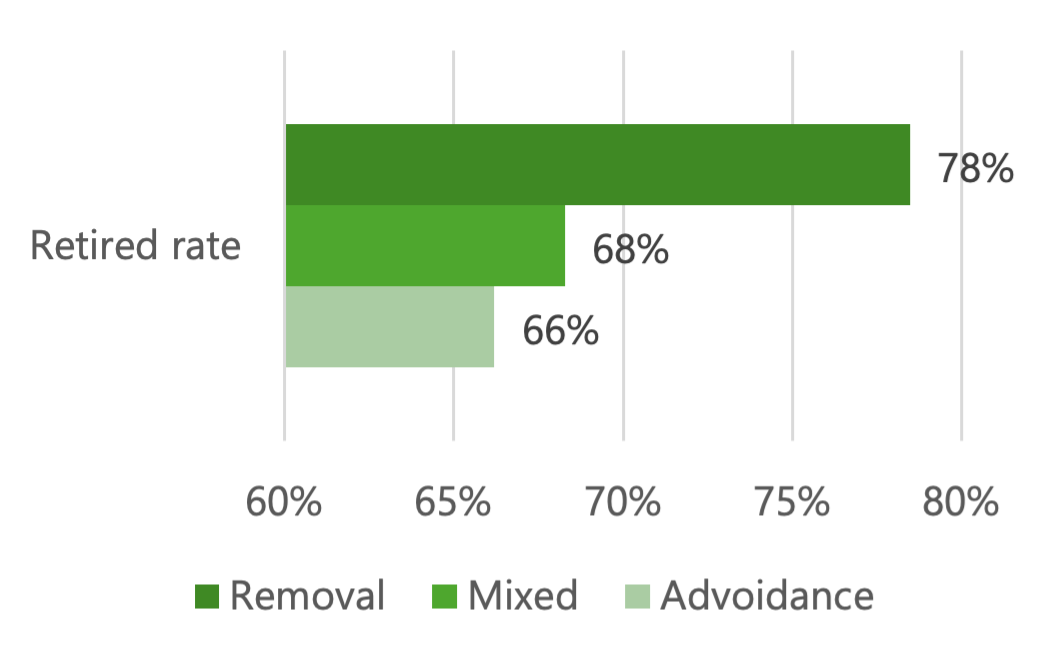

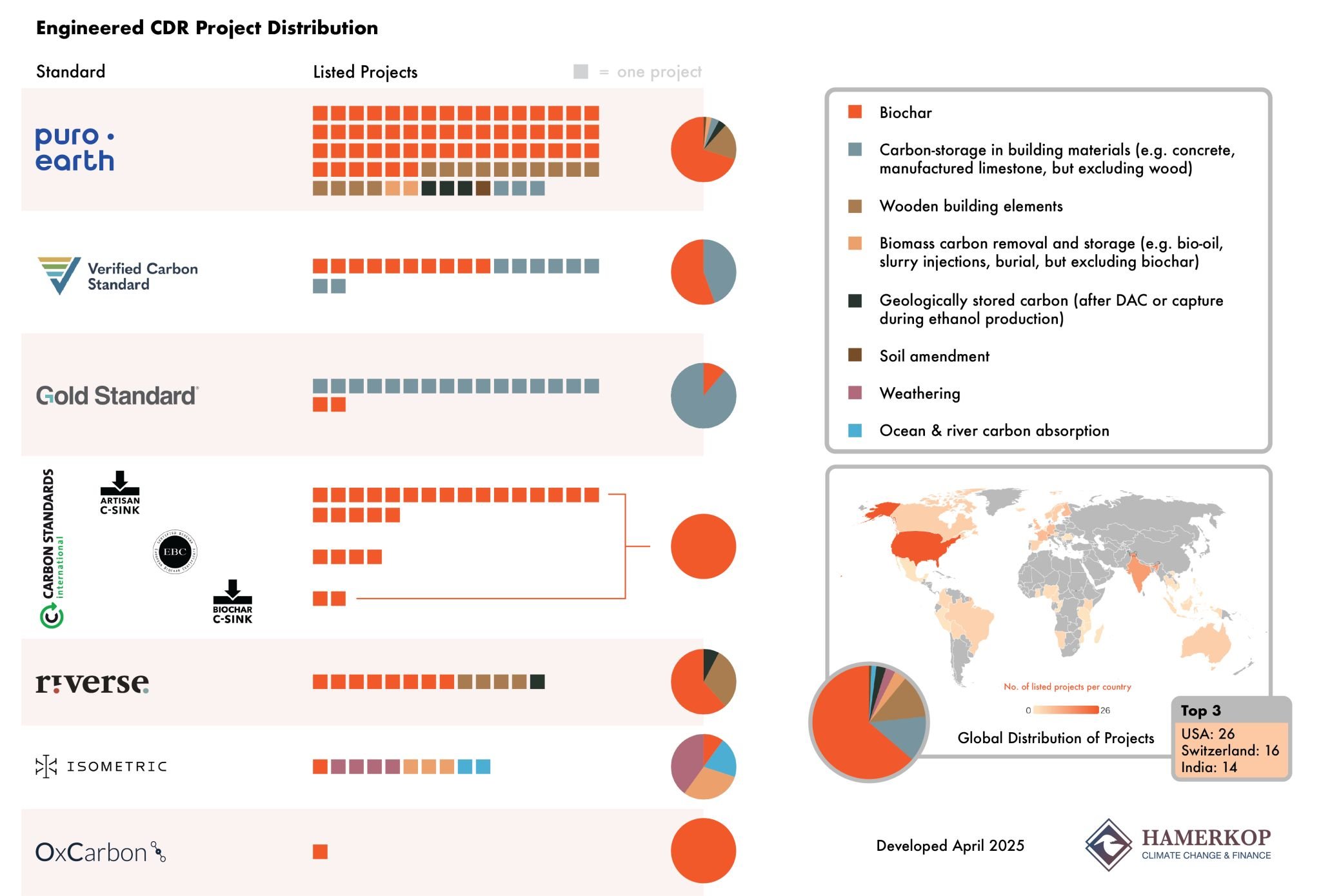

To gain an overall understanding of the landscape of NbS policy/strategies in these countries, we first looked at a country-by-country snapshot (as of September 2025) of how the carbon certification standards are recognized and used for NbS across the five Southeast Asian markets, as seen in the infographic in Figure 1.

Figure 1 - Southeast Asia Certification Standard Recognition and Usage

Note: The infographic reflects the status of certification standards as of September 2025. Since then, the regional landscape has evolved rapidly. However, the accompanying text has been updated to incorporate the latest developments.

Each row lists a standard, and each column shows that standard’s status in each country, whether it has official acknowledgement/policy alignment and, crucially, whether there are actual registered NbS projects on the ground. In short, it pairs policy acceptance with real deployment. Recognition currently outpaces implementation as many standards are acknowledged by governments but have no registered NbS projects yet. Actual activity clusters around a small set of widely used programs (notably VCS and, for non-REDD+ projects, Gold Standard), while newer or niche standards (e.g., Equitable Earth, Cercarbono, Isometric, ICR, OxCarbon, Social Carbon, BioCarbon) are present but largely await their first projects in most countries. The suitability of certification standards were assessed based on their:

Alignment with existing policies/strategies: here defined as any officially written document by government authorities that support or restrict the promotion of NbS related activities and the use of certain certification standards in the country. This also accounts for any ongoing official recognition of a certification standard by government authorities. The current use of a certification standard in a country was assessed as a sign of unofficial endorsement in that context.

Alignment with NDC priorities: notably how well certification standards are adapted to NbS project types prioritized by the country. For example, if Indonesia’s NDC prioritizes REDD+ projects, then certification standards with REDD+ methodologies were considered more suitable than those without such methodologies.

The current analysis did not consider technical details such as monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV), benefit-sharing, or environmental and social safeguards requirements. In cases where the NDC does not show NbS priorities, the most common project type on the ground was considered as the priority project type.

Based on this approach, we mapped each region’s landscape of policy/strategy and NDC targets to highlight how certification standards may align and where gaps remain:

Indonesia

The foundation of the VCM is the Presidential Regulation No. 98 of 2021, which defines the Carbon Economic Value (NEK) and introduces key mechanisms such as carbon trading, result-based payments, and a potential carbon tax. The regulation identifies the forestry and land use sector as the primary source of potential for emission reductions, with nearly 60% of Indonesia’s NDC targets expected to be met through restoring 2 million hectares of peatlands and rehabilitating 12 million hectares of degraded land under the FOLU Net Sink 2030 initiative. To operationalize this framework, the government issued a procedure for carbon trading in 2022, outlining the procedures for carbon trading and the certification of emission reductions through the SRN-PPI registry. This was followed by a regulation in 2023, providing sector-specific guidance for carbon trading in forestry, including MRV processes and the issuance of verified emission reduction certificates (SPE-GRK). In 2023, Indonesia also passed a law classifying carbon units as financial securities and mandated the creation of a carbon exchange, under the IDX Carbon platform. Indonesia has also signed Mutual Recognition Agreements with the GS, the VCS, Plan Vivo and GCC, allowing the projects certified under these standards to be registered to the SRN-PPI, without duplication of process, streamlining registration and oversight. Indonesia’s carbon projects are dominated by REDD+, which accounts for approximately 80% of activities, followed by afforestation/reforestation and wetland restoration.

Malaysia

Malaysia’s carbon market policy landscape is still under development. Two key documents, the National Guidance on Voluntary Carbon Market Mechanisms and the National Guidance on Forest Carbon Market are both non‑binding frameworks meant to steer the operation of voluntary carbon trading and forest‑based carbon activities. The first outlines how entities can voluntarily buy and sell credits to offset emissions; the second gives reference points for any state or organization planning forest carbon projects. Launched in 2022, the trading platform for carbon credits is the Bursa Carbon Exchange (BCX), operated by Bursa Malaysia, as a joint push by the finance and environment ministries to support net‑zero goals. BCX currently only promotes credits certified under Verra’s VCS or the Gold Standard. Participation is voluntary, and an ETS or carbon tax is still under development. Malaysia’s latest NDC does not make room to engage in Article 6 voluntary cooperation. Because land and forests fall under state control, state governments decide whether to allow carbon projects, making federal-state coordination essential for nature‑based initiatives. States like Sarawak and Sabah already have (or are developing) their own jurisdictional rules.

Thailand

Thailand’s 20‑year National Strategy and the 13th National Economic and Social Development Plan set the policy direction for the economy and development, including the country’s climate goals. These plans influence how carbon market mechanisms are integrated into national priorities, such as the development of the Thailand Voluntary Emission Reduction (T‑VER) program and its premium T‑VER credits, which offer higher-value offsets with additional environmental and social co-benefits. Alongside the T-VER, Thailand also launched the Voluntary Emissions Trading Scheme (V-ETS) in 2013, mostly covering renewable energy, efficiency, and waste; a national ETS is planned to take place once the Climate Change Act is passed (around 2028-29). Thailand’s energy and climate planning relies on national strategy documents and sector-specific plans. While the country updated its energy targets in 2018, these have not yet been formally adopted into the overarching national blueprint, so they continue to serve as the most relevant reference point for ongoing policy discussions. Thailand has committed to carbon neutrality by 2050 and to net‑zero by 2065, but these are not yet legally adopted and are expected to be embedded in the forthcoming Climate Change Act, alongside a developing national registry. As it stands, Thailand does not yet have concrete policies that specifically support or prioritize NbS. Instead, its current strategies remain heavily focused on the energy sector.

Cambodia

Cambodia’s Climate Change Strategic Plan 2024-2033 (CCSP) is the country’s blueprint for achieving its NDC and the roadmap that identifies objectives for each sector, setting adaptation and mitigation priorities. The CCSP complements the Long-Term Strategy for Carbon Neutrality which serves as a vision document for carbon neutrality in 2050. The Royal Government of Cambodia in the NDC, strongly supports REDD+ and has adopted the National REDD+ Strategy, aiming to cut annual deforestation by half from the 2006–2014 average rate of 1.5% per year. However, Cambodia does not currently have a national carbon credit registry, ETS or carbon tax, but is currently progressing towards the creation of a Sub-Decree, that will likely require carbon crediting initiatives to register with the national carbon credit registry that will soon be operational and released publicly. The Ministry of Environment has approved an “Operations Manual” for implementing Article 6 of the Paris Agreement which provides a framework for issuing and transferring ITMOs, although it has not been legislated yet. Cambodia is now piloting an early stage nested REDD+ system with the Jurisdictional & Nested REDD+ (JNR) methodology from VCS, which will let the government set an overall baseline for emissions and then give each REDD+ project its share of that baseline. The system is guided by draft rules (Prakas) and clear instructions for how projects should fit into it, covering elements such as project eligibility, MRV, safeguards, registry rules, and fair benefit-sharing. Cambodia introduces a draft list of the methods that projects can follow and get approved, featuring VCS JNR and standalone VCS REDD+ methodologies.

The Philippines

The carbon market landscape in The Philippines is not fully operational, with key policies and frameworks still being developed. The Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Climate Change Commission, and Department of Finance are actively working on essential components, including a national carbon registry, MRV infrastructure and process, sector-specific benchmarks, and social and environmental safeguards. A comprehensive policy framework is expected by late 2025, with the system becoming fully operational by February 2026. At present, policy development is more advanced in the energy sector—regulated under the Philippine Energy Plan 2020–2040—given its higher emission levels, while forestry sector guidelines are still being formulated. Uncertainty remains around forest emissions data and for instance, in 1994 emissions were nearly zero, but by 2000 forests appeared to absorb 105 MtCO₂ per year, a figure that dropped to 37 MtCO₂e per year by 2010. These shifts largely stem from evolving forest definitions and improvements in data methodology, indicating reliability issues with past estimates. Forestry targets are scarcely mentioned in the country’s NDC, without further measurable actions, making the energy sector a focus, with no progress on REDD+ readiness. The NDC targets also exclude the Land Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry sectors. However, there are several ARR and upcoming REDD+ projects, primarily under the VCS and GS.

The Southeast Asian carbon market is diversifying and operationally becoming nuanced. Success for businesses and stakeholders lies in understanding not just the technical requirements of a certification standard, but its political and regulatory compatibility with the host country’s specific climate strategy.